A Challenging Case of Chemoresistance in Locally Advanced Breast Cancer

Abdullah Mohammed Alshamrani, Suhaib khalid Alothmani, Mohammed Mousa Dahman, Abdulaziz Abdullah Howil, Abdulrahman Jaman Alzahrani*

General Surgery Department, Security Forces Hospital Program

*Corresponding author: Abdulrahman Jaman Alzahrani, General Surgery Department, Security Forces Hospital Program, P.O. Box 3643, Riyadh 11481 Saudi Arabia. Email: a-alrahman@hotmail.com

Citation: Alshamrani AM, Alothmani SK, Dahman MM, Howil AA, Alzahrani AJ (2020) A Challenging Case of Chemoresistance in Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. Annal Cas Rep Rev: ACRR-102.

Received Date: 06 March, 2020; Accepted Date: 11 March, 2020; Published Date: 17 March, 2020.

Abstract

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the standard of care in inoperable locally advanced breast cancer (LABC), as it helps in reducing tumor burden and facilitating surgical resection. We describe a 56-year-old post-menopausal woman who presented with a huge, right breast mass extending from the clavicle to the mid abdomen. A chest-abdomen-pelvis computed tomography showed the mass invading the pectoralis muscles and right axillary lymph node with no evidence of distant metastasis. A needle core biopsy revealed an infiltrating ductal carcinoma (Scarff-Bloom- Richardson grade 3). A multidisciplinary collaboration was undertaken, and the patient was started on docetaxel; however, after three cycles of docetaxel, she showed no improvement and was readmitted for palliative mastectomy with skin grafting. A post-operative histopathology examination of the excised tumor revealed an invasive micropapillary carcinoma. A multidisciplinary approach is the cornerstone for the treatment of LABC. In the case of chemoresistance, very few treatment options are available.

Keywords: breast cancer, breast neoplasm, chemotherapy resistance, docetaxel.

Introduction

Breast cancer treatment depends on the stage of the disease and pathologic characteristics of the primary tumor, including tumor receptor status and grade. Patients are considered to have a localized disease if there is no clinical or radiological evidence of remote metastasis [1].

However, many patients with locally advanced breast cancer will relapse after tumor resection if they do not receive systemic therapy [2]. Several factors determine whether a patient with locally advanced breast cancer will relapse, including primary tumor size, number of axillary lymph nodes involved, and histological characteristics of the primary tumor [3].

The management of locally advanced breast cancer poses a lot of challenges to clinicians. Recently, it was reported that neoadjuvant chemotherapy is beneficial in locally advanced disease in that it can effectively eradicate subclinical disseminated tumoral lesions, thus improving the long term and disease-free rates in these patients [3]. Unfortunately, resistance to chemotherapy complicates treatment in locally advanced breast cancer.

Chemoresistance to an anthracycline and/or a taxane is common in patients who receive one or both agents [4]. Some patients who receive a single, anti-neoplastic agent for an extended period may develop resistance to several other structurally unrelated compounds, further complicating treatment, as few treatment options are available for patients who develop chemoresistance to these drugs. After anthracycline- or taxane-based chemotherapy failure, capecitabine, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, or albumin-bound paclitaxel may be offered to these patients [4].

Despite salvage therapy with capecitabine as a single agent, or in combination with another chemotherapy agent, the response rates in these patients are still low and range from 20–30%, with a median duration of response of less than six months [5,6]. Additionally, salvage therapies do not always yield results that translate into improved long-term survival.

We present the case of a patient with locally advanced breast cancer who failed to respond to three cycles of taxane-based chemotherapy and palliative mastectomy was performed as a result.

Case Presentation

This is the case of a 56-year-old, post-menopausal woman who, in October 2016, presented to the breast and endocrine clinic of our institution after noticing a breast mass the size of an olive, which increased with time. In August 2017, the patient’s family noticed the breast swelling had increased, and she started complaining of pain and a hot sensation over the right breast. Her medical and surgical histories were unremarkable. She reported a history of anorexia and weight loss and had a history of breastfeeding. She had no family history of breast cancer, oral contraceptive use, trauma, or exposure to radiation.

On physical examination, the patient was mildly cachectic and nervous and had stable vital signs. A local examination of the right breast showed a huge mass extending from the clavicle to the mid abdomen, which restricted the patient’s daily activities (Figure 1). The mass was tender and hard in consistency. Also, there was a palpable right axillary lymph node, which was firm and mobile. There was no discharge or clinical evidence of metastasis.

Figure 1: Huge breast mass extending from the clavicle to the mid abdomen.

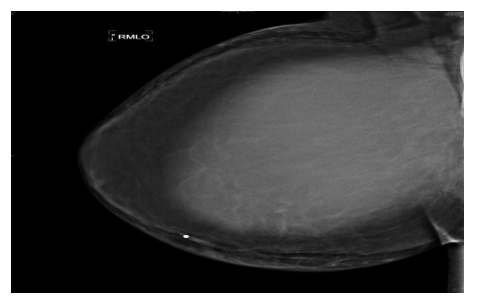

A mammography was performed, and it showed a huge isodense, fairly well-defined mass occupying most of the right breast, with enlargement of the breast. It measured approximately 20 cm in its largest dimension (Figure 2). The overlying skin was thickened, and no microcalcifications were observed. The axillary regions could not be included in the examination; however, some lymph nodes were noted.

Figure 2: Huge, fairly well-defined, isodense mass occupying most of the right breast with enlargement of the breast. The mass measures approximately 20 cm in dimension and is associated with thickening of the overlying skin. No microcalcifications present.

An ultrasound examination of the right breast showed a fairly well-defined, large, complex, heterogeneous mass showing some vascularity. It measured approximately 16 cm in its largest dimension and occupied most of the right breast (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Fairly well-defined, large, complex, heterogeneous mass showing some vascularity. The mass measures approximately 16 cm in dimension and occupies most of the right breast.

A chest-abdomen-pelvis computed tomography showed the mass invading the pectoralis muscles and right axillary lymph nodes (Figure 4). There was no evidence of distant metastasis.

Figure 4: A chest-abdomen-pelvis computed tomography shows the mass invading the pectoralis muscles and right axillary lymph node.

A core needle biopsy was performed, and a histopathology examination revealed infiltrating ductal carcinoma, with a Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grade of 3/3. There was no in situ component, lympho-vascular or perineural invasion, and no microcalcification. Furthermore, the tumor was estrogen-receptor-, progesterone-receptor-, and HER2-negative; the Ki-67 index was 60%.

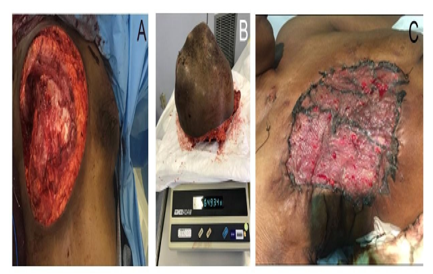

A multidisciplinary collaboration was undertaken, and the patient was started on chemotherapy. After receiving three cycles of chemotherapy with docetaxel, the patient showed no improvement. After failure of chemotherapy, she was readmitted for a palliative mastectomy with skin grafting (Figure 5). A post-operative histopathology examination of the excised tumor revealed invasive micropapillary carcinoma of the right breast with necrosis. The tumor measured 27 cm in its largest dimension. Negative margins were achieved, and the lymph node ratio was 10/18. The patient did well, and her post-operative course was uneventful. A skin graft was obtained, and it had a viability of 90%. She was discharged on the sixth day post-operative and was followed up at the oncology, breast and endocrine clinics.

Figure 5: Gross appearance of the right chest wall (A) and tumor (B) after breast resection. Skin grafting was performed after mastectomy (C).